Pulotu, Hawaiki and Lapita Featured

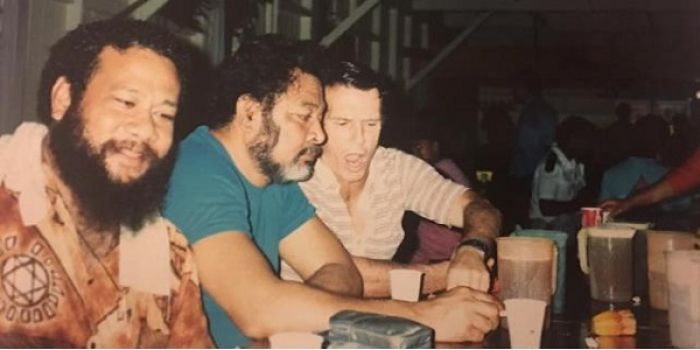

Left to right - Professor Hufanga ‘Okusitino Mahina, Late Professor Epeli Hau’ofa, Professor Randy Thaman (Husband of Konai Helu Thaman)

Left to right - Professor Hufanga ‘Okusitino Mahina, Late Professor Epeli Hau’ofa, Professor Randy Thaman (Husband of Konai Helu Thaman)

KOLOMU ‘ILO, FONUA & TALA (TALAEFONUA, HALAEFONUA & VAKAEFONUA), (KNOWLEDGE, CULTURE & LANGUAGE COLUMN)

Pulotu, Hawaiki and Lapita

The imposition of names by early explorers and later by scholars on to places across

Moana has been highly problematic. The ancestral islands of Pulotu and Hawaiki, for example, are now called ‘Lapita’ by both archaeologists and linguists. Lapita is a place in New Caledonia where fragments of highly decorated, elaborate and beautiful pottery have been found. These were thought to have been associated with the original Moana people, who are now also called the Lapita people. But designating Pulotu and Hawaiki as ‘Lapita’ is a huge problem. Pulotu and Hawaiki were once centres of intense cultural development, where refined knowledge, skills and technology were transferred through trade and exchange.[i] By contrast, Lapita was and is merely a single place in New Caledonia.

However, it is in raising problems that solutions can be found, and a similar examination can be made for other names. I use the indigenous, locally mediated name ‘Moana’ in place of the foreign, externally imposed label ‘Pacific’.[ii] As a huge expanse of ocean, the moana was far from peaceful, the connotation implied by ‘Pacific’. Moana was in fact a place of connection, separation and intersection; of life and death, nourishment and malnourishment. Moana navigators and fishermen were generally called tautai (warriors of the sea) or kaivai (eaters of the water), terms which evoke imagery of a permanent war waged against the elements and a constant state of oneness with waves and winds through effective knowledge and skills. These names point to Moana as a place that both connects and separates – that is, intersects – rather than a space that only connects.

Similarly, Moana was divided by earlier ethnographers into the regions of Melanesia, Polynesia and Micronesia, meaning ‘islands of dark-skinned people’, ‘many islands’ and ‘small islands’ respectively. So-called Polynesia was further divided into western Polynesia and eastern Polynesia. Oddly, the naming of Melanesia was driven by race and geography, and that of Polynesia and Micronesia by size and geography. Why was Melanesia not named Macronesia, given that in both size and geography it is made up of ‘large islands’? I propose that the names Melanesia, Polynesia and Micronesia should be changed to and replaced with Macromoana, Polymoana and Micromoana respectively.

The European names resulted because explorers of earlier eras – like many scholars of the current era – did not take local knowledge, cultures and languages seriously and sensitively. Oral histories (communicated and transmitted by word or sound of mouth) were and are often contrasted unfavourably to written history (communicated and transmitted by word or marking of pen), though there is no hierarchical or vertical need to differentiate them by status, merely to accept their logical or horizontal / historical difference – that is, their respective means of communication and transmission.[iii]

According to the oral history of Moana Oceania, the islands and peoples are generally thought to have originated in the ocean, out of which emerged by transformation the first lands, flora, fauna, humans and gods.[iv] Based on cultures, languages and refined knowledge and skills, both material and non-material, western and eastern Polynesia can now properly be called Moana hihifo (western Moana) and Moana hahake (eastern Moana), with Pulotu and Hawaiki as their respective regional ancestral homelands and afterworlds. Pulotu and Hawaiki – situated roughly somewhere in the Lau Islands in Fiji and in the Cook Islands in Moana lotoloto (central Moana) – are both said in oral history to be actual islands lying to the northwest of all inhabited islands.

In Moana, refined knowledge and skills acquired through education are constituted or composed in culture (the receptacle), and transmitted or communicated in language (the vehicle), as temporal-spatial entities taking place in tā (time) and vā (space). In this intellectual process, mind and thinking are dialectically transformed from vale (ignorance) to ‘ilo (knowledge) to poto (skill), with knowledge production taking precedence over knowledge application.[v] Some forms of knowledge, that is, historical kernels, are wrapped up in symbols by means of the performance arts of mythology, story, poetry and oratory. The merging of history with mythology is done by means of heliaki, which involves speaking one thing but meaning another – an artistic and literary device for distinguishing between the symbolic and the realistic.

In plural, tempo-spatial (and formal-substantial), collectivistic, holistic and circular ways, the transmission or communication of refined knowledge and skills in Moana is both temporally–formally defined or marked and spatially–substantially composed in culture and language. The past and the future – located respectively in front of people as guidance (the past) and behind them, where the yet-to-take-place is made to be informed by past experiences (the future) – are constantly mediated in the ever-changing, conflicting present. The same applies to Pulotu and Hawaiki, which can be meaningfully mediated on their own terms rather than by way of the meaningless, senseless and insensitive imposition of ‘Lapita’. When translating knowledge and skills across cultures and languages, we must seek a logical shift from the condition of imposition to a situation of mediation, where intersections, connections and separations symmetrically create a sense of sustained harmony and beauty of scholarship in the intellectual and creative process.

Endnotes

[i] ‘Ōkusitino Māhina, ‘The Tongan Traditional History Tala-e-fonua: A vernacular ecology-centred, historico-cultural concept’, PhD thesis, Australian National University, Canberra, 1992.

[ii] See, for example, ‘Ōkusitino Māhina, ‘Tā, Vā and Moana: Temporality, spatiality, and indigeneity’, Pacific Studies, special issue, vol. 33, no. 2/3, 2010, pp. 168–202.

[iii] Māhina, ‘The Tongan Traditional History Tala-e-fonua’.

[iv] Albert Refiti, ‘Mavae and Tofiga: Spatial exposition of the Samoan cosmogony and architecture’, PhD thesis, Auckland University of Technology, 2015.

[v] ‘Ōkusitino Māhina, ‘From Vale (Ignorance) to ‘Ilo (Knowledge) to Poto (Skill), the Tongan Theory of Ako (Education): Theorising old problems anew’, AlterNative: An International Journal of Indigenous Peoples, vol. 4, issue 1, 2008, pp. 67–90.

Further Reading

Geraghty, Paul, ‘Pulotu, Polynesian Homeland’, Journal of the Polynesian Society, vol. 102, no. 4, 1993, pp. 343–84.

Source

Crafting in Aotearoa: A Cultural History of Making in New Zealand and the Wider Moana Oceania (2017), edited by Karl Chitman, Kolokesa U. Māhina-Tuai, and Damian Skinner and published by Te Papa Press, Wellington, Aotearoa New Zealand.

Hūfanga He Ako Moe Ako, Dr ‘Ōkusitino Māhina, Professor of Tongan Philosophy, Anthropology and Art, Vava‘u Academy for Critical Inquiry and Applied Research, Kingdom of Tonga & Vā Moana: Space and Relationality in Pacific Thought and Identity, Marsden Inquiry and Research Cluster, AUT University, Aotearoa New Zealand.