A Mural Reimagines the History of a 19th-Century Tongan Club Featured

Benjamin Work in "Walking Backwards into the Future"

Benjamin Work in "Walking Backwards into the Future"

13 November, 2018. Auckland-based artist Benjamin Work painted a Manhattan mural that activates the narrative history of a Tongan club in the Metropolitan Museum of Art.

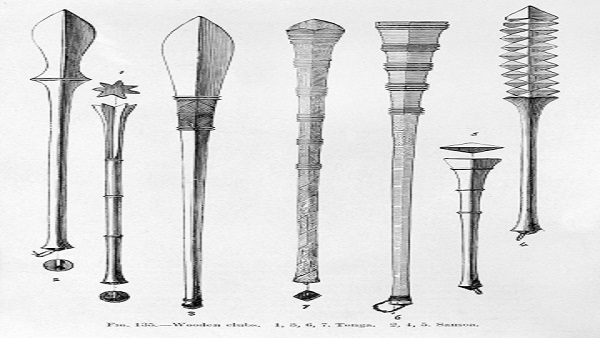

The 19th-century clubs from Tonga now in the collections of the Metropolitan Museum of Art were created as narrative objects, their carvings evolving to tell the story of the people who wielded them.

Rarely were these personal histories collected by museums along with this weaponry from the South Pacific. In his art, the Auckland-based Benjamin Work reimagines the sculpted motifs and stories of these clubs, as well as other traditions of his Tongan (Vava’u) heritage, in paintings, photography, and murals.

“Tongan visual language is ancient and abstract in form, primarily influenced by nature, with intricate knowledge systems intertwined within,” Work told Hyperallergic. “My interest started as a child with the presence of Ngātu, Tongan bark cloth, and Fala, woven mats, in our family house. Every bed in my parents’ home had ngātu or fala, folded neatly under all the mattresses; these spaces were perfect to keep them safe and flat.”

While early in his practice he was mostly engaged with graffiti and street art, in 2010 he began to explore different media. “This led me back to our ancient semiotic language of Tonga,” he explained.

In 2016, he created a mural at the PS 171 school on 103rd Street and Madison Avenue, a site that already featured a ring of birds by the Cape Town-based street artist FAITH47, and a take on the Statue of Liberty by street artist Sego Y Ovbal of Mexico City.

The visuals of Work’s red and black piece — called “Tauhi Vā” — came directly from his time at the Metropolitan Museum of Art, where he connected with Dr. Maia Nuku, associate curator for Oceanic art. “We explored the Tongan treasures within the Met’s collection, and from our interaction and dialogue with the treasures, ideas were manifested,” Work stated. “These are not static objects in a storeroom but living treasures that tell stories, stories of who we were, and who we are.”

Their collaboration is the focus of Walking Backwards into the Future, a short film by Anna Weinreich.

Weinreich directed it as part of the Program in Culture and Media in New York University’s Department of Anthropology, and it recently screened in the Margaret Mead Film Festival’s Emerging Visual Anthropologists Showcase at the American Museum of Natural History.

In its 12-minute run, the film travels from New Zealand to New York, with both Work and Nuku discussing the significance of the Tongan objects as living culture. In one scene, Nuku walks through the Oceanic art galleries at the Met, where ancestor poles from the Asmat people of New Guinea join a carved temple drum from the Austral Islands.

“All the art in the gallery is really a means to story, a means to pass on knowledge from one generation to another, so the oral traditions that are so vital in the Pacific, they’re all embedded in the artworks,” Nuku says in Walking Backwards into the Future, affirming that “these ancestral treasures” are not “passive objects.”

With Nuku, Work led a tour in the gallery, and spent some time in the Met collections examining the Tongan clubs. He was drawn to a carving of two warriors reaching out to each other, coming together between a diamond shape, and incorporated these dynamic figures into his large-scale interpretation.

Work’s completed mural is alongside a basketball court, with the film overlapping the rhythmic sound of Polynesian tattooing with the dribbling of a ball.

Manhattan is a long way from Tonga, but so are the Tongan clubs far from their original home. Work’s mural continues the club’s life as a narrative object, now in this New York City context.

Both his art and Weinreich’s film are a conversation with the past that looks ahead to new relationships with museum artifacts, making them part of active space.

- hyperallergic.com