Restoring a Tongan ngatu hingoa (barkcloth) commemorating WWII Featured

Restoring a Tongan ngatu hingoa (barkcloth) commemorating WWII by: Anne Peranteau

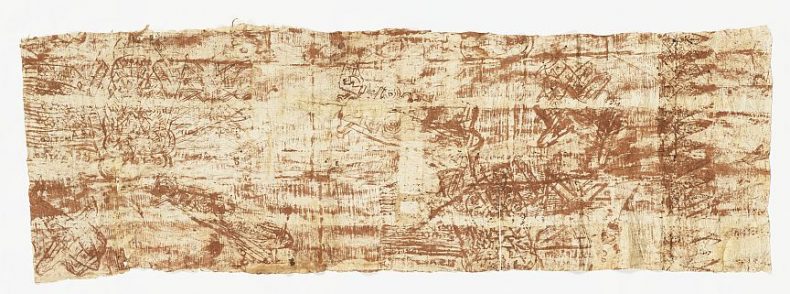

Conservator Textiles Anne Peranteau recently completed the conservation treatment of an important Tongan ngatu hingoa, or barkcloth, that commemorates the WWII war effort of Queen Sālote Tupou III and the Tongan people.

The ngatu

A total of £15,000 was raised in Tonga for the British to buy the Spitfire airplanes, which were named Queen Sālote (the aircraft depicted on the tapa), Prince Tungi, and King Tupou I. At least two of the Spitfires saw service in battle (read more about the history of the three planes).

The planes were not the only form of support for the Allied cause by early 1941 the Tongan Defence Force was made up of 2,700 men with an additional 10,000 Home Guards.

The maker or makers of the ngatu have carefully depicted a view of the plane as seen from below, capturing the elliptical shape of the wing that was the key to the nimbleness and overall success of the plane in battle, most famously the Battle of Britain.

The commemorative barkcloth is part of what would originally have been a larger piece. The “28” at the left side refers to a unit of measurement called a langanga; one ngatu in Te Papa’s collection with 50 langanga is over 22 metres long. Ngatu were cut down to enable smaller pieces to be distributed as gifts.

While we unfortunately don’t know who made this ngatu, it is recorded that it passed through the hands of the family of a United States serviceman who was in the Pacific during the Second World War. Personally, I find it a fascinating piece that combines the contemporary and traditional, attesting to the ways that conflict brings cultures in contact with each other.

Barkcloth materials and construction

The ngatu consists of two layers of beaten inner bark from the mulberry tree (Broussonetia papyrifera), one of several plant species used for making tapathroughout the Pacific.

The two layers have been adhered together in select areas, possibly using arrowroot or tapioca starch, but the adhesion is not uniform across the entire ngatu and in many areas the layers are not joined.

The decoration in shades of brown probably employs dyes and saps extracted from local trees like the candlenut (Aleurites moluccana).

Condition

When the ngatu was acquired, it was identified by the collection manager and curator as a priority for treatment due to its obvious fragile condition.

There were many cuts and tears that went through the top layer or both top and bottom layers. Creases near the torn areas distorted the legibility of the design and there were also dark orange-yellow rectangular stains associated with five of the tears.

On the basis of the colour, shape, texture, and position of these stains, they were identified as aged residue from masking tape.

The tape itself was disintegrated and was not doing any of the work of holding the tear edges together.

The overall goals of conservation treatment were to stabilise tears to reduce risk of any further damage from handling (for example when rolling it for storage) and display, and to remove as much as possible the stains caused by adhesive residue.

Tape

Pressure-sensitive tape was first developed in 1845 by a surgeon, Dr. Horace Day, who used natural rubber on a cloth substrate to create a surgical tape. Masking tape was invented 80 years later by 3M, a company which continues to market dozens of different tapes today.

The unsightly staining caused by aged natural and synthetic rubber adhesives is accompanied by the formation of formaldehyde and peroxides which weaken the underlying material.

The residue also interferes with the attachment of a more effective and suitable material for mending the tears. Stain removal was pursued for the benefits to the ngatu’s appearance and also for promoting its long-term preservation.

Tape removal

For removal of the tape it was necessary to use solvents that would dissolve the residue, without affecting the dyes used to make the design. The solvents were also selected according to the degree of oxidation (ageing) that the tape had undergone.

The solvents were combined with a synthetic polymer to create a customised gel material.

The main benefit of using a gel is that the solvents are held in contact with the aged rubber residue for a longer period of time before evaporating, so less solvent is needed to remove the staining.

The gel also acts like a poultice so that when applied, it can be observed turning a darker yellow as the staining material below is solubilised and drawn up into the gel.

The majority of the adhesive residue was removed this way.

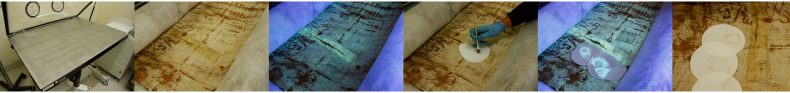

Following the gel step, liquid solvents and water were used to further reduce staining. The sequence of images below shows this process; adhesive residue can be easily visualised under ultraviolet light because of its chemical structure.

Areas where there is more adhesive residue fluoresce a bright yellow-green. As the solvent is applied, the residual adhesive and gel are transferred to the underlying blotter paper so that none remains in the ngatu.

Tear repair

The final step in the treatment was to align and mend creases and tears.

Tears have been mended with a combination of Japanese kozo paper (which is made from the same mulberry bark fibres as the ngatu) and a transparent non-woven fabric.

The non-woven fabric is dyed so that it is barely perceptible against the ngatu. Areas where the top layer of barkcloth have been lost, like the lower right, where the original material is missing, were not restored.

The goal in this case is not to return the ngatu to a like-new appearance but to prevent further damage and to remove visually detracting staining.

Adhesives used to attach the repair materials are ones widely used in conservation because they are known to have excellent long-term stability.

They are not “off the shelf” proprietary formulations, so all ingredients are known. Unlike the rubber adhesive in masking tape, they do not discolour or become brittle and they are easily reversed using water or solvent.

Adhesives and dyes used in the conservation process are distinct from the materials that would have been used traditionally in order to make it obvious what repairs are traditional and what material is a later addition.

The ngatu is in a much better state for display and we hope the opportunity presents itself soon.

Thanks to intern Kimi Taira (now the Assistant Conservator for Works on Paper at the Asian Art Museum, San Francisco) for assistance in the early phases of this treatment work.

-Museam of New Zealand